Leitmotif

Table of Contents

- Designing leitmotifs: Lord of the Rings

- Unifying Music and Narrative

- Development of Leitmotifs

- Bibliography

Key Takeaways

- This chapter is based on Bribitzer-Stull (2015).

- A leitmotif is a theme that is associated with (often) a character in a piece of media that develops alongside the character’s own development.

- Not every prominent theme is a leitmotif: the theme must be developed to be a true leitmotif.

- Leitmotivic analysis must address both musical content and dramatic content.

Leitmotifs, originally associated with Wagner, are defined by Bribitzer-Stull (2015) as a musical theme composed of musical and emotional elements that gets developed alongside the dramatic development within the film.

Many media scores nowadays will assign important characters their own musical themes that recur each time the character is featured. This practice went in and out of fashion for a time, but resurged in the mid-1970s thanks to films like Star Wars, and has remained a popular approach to media scoring.

Designing leitmotifs: Lord of the Rings

Before defining in detail what a leitmotif is and how it is used in film, we will begin with some concrete examples of leitmotifs in a well-known film trilogy: Lord of the Rings.

This analysis summarizes Bribitzer-Stull (2015), 294-299.

4̂ in Lord of the Rings leitmotifs

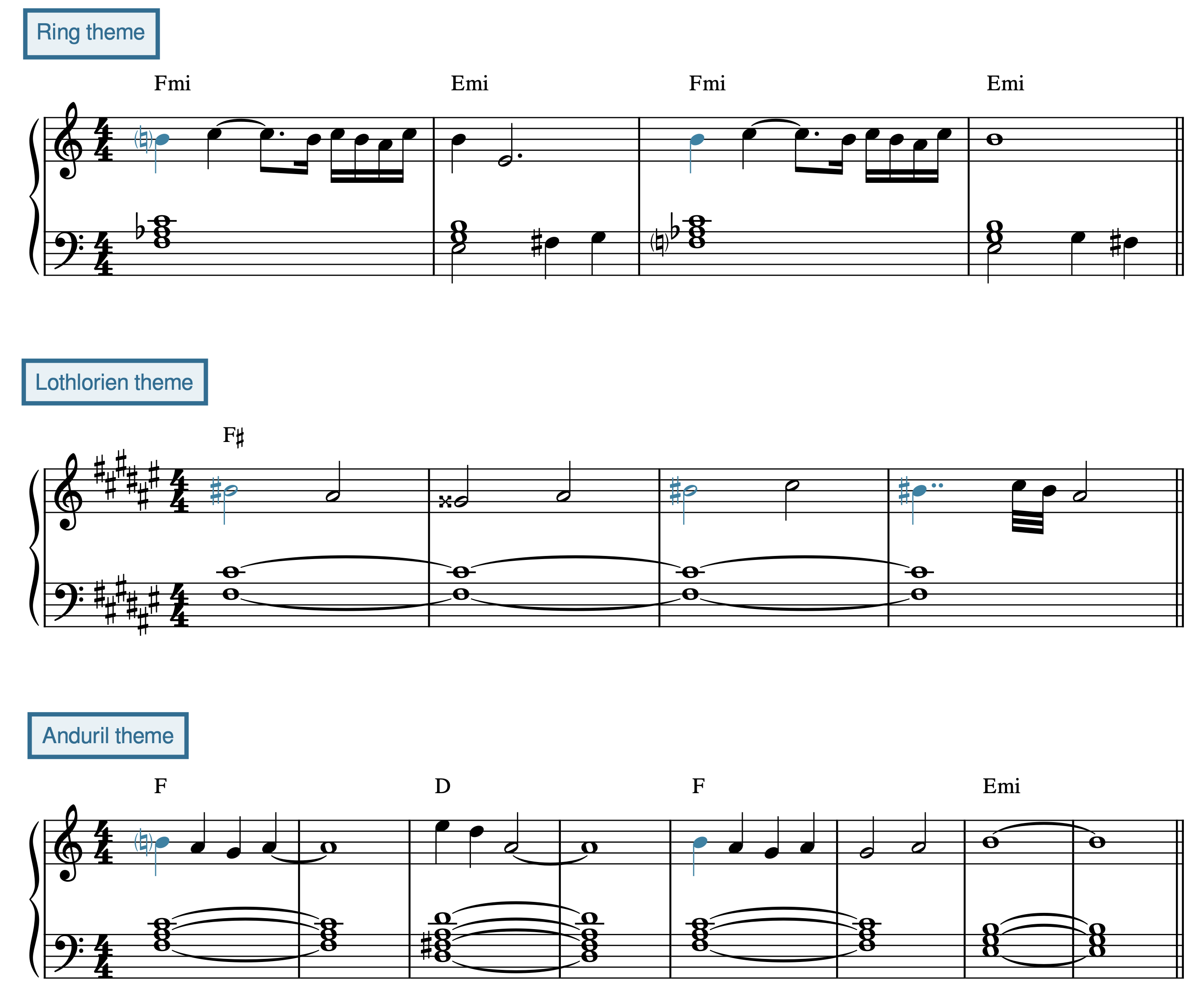

Example 1 below gives simple transcriptions of the melody and harmony of several prominent themes in the Lord of the Rings soundtrack which emphasize fi (♯4̂) in the melody. There are still other themes that also emphasize fi not included here—”Sorrow of the Elves” and “Dwarves of Yore.”

As we discussed in the Topic Theory chapter, fi is often topically associated with magic. Indeed, each of the themes in Example 1 are associated with something magical, and with a “more-than-human race” (296). The Ring of course is imbued with evil magic; Lothlórien is an enchanted forest (tied to the magic of another Ring of Power) and home of a clan of elves; Andúril is an enchanted and legendary sword wielded by the Númenórean hero Aragorn. These themes also all feature non-functional triadic harmony, favoring planing and chromatic mediants over tonic–dominant relationships.

Contrast this with the “Shire” theme, which represents the hobbits. The hobbits are the main protagonists of The Lord of the Rings; we are meant to identify with them as regular folk (as opposed to the elves, dwarves, orcs, and even humans in the Lord of the Rings universe). The harmony is simple and functional; the melody is firmly major. Notably, it avoids fa (4̂) except as a brief upper neighbor embellishment.

These themes saturate the first two films, and even most of the third, creating a sound world in which fa is reliably raised to fi in several themes signifying the supernatural, and the most down-to-earth theme—that of the Hobbits—avoids fa and fi alike.

Into the West

The final leitmotif of the Lord of the Rings trilogy is “Into the West” (Example 2), introduced in the third film, The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003). Note that this leitmotif repeatedly uses fa–mi as a melodic motive—”inverting the earlier ♯4̂–5̂ motive and filling in the ‘Shire’ theme’s missing 4̂” (298). Emotionally, this leitmotif signifies the end of the central good-versus-evil drama of the trilogy and a return to normalcy for the Hobbits (and everyone else).

The leitmotif appears in full during the emotional scene when Frodo sails into the West, leaving behind the other Hobbits (most importantly, Sam, his closest companion) to journey to the Undying Lands, where the Elves live out their days after their time on Middle Earth.

This theme is foreshadowed only twice before its full statement at the very end of the film. During a battle, the wizard Gandalf tells the Hobbit Pippin what happens after death; the leitmotif here signifies the heavenly afterlife that Gandalf describes. A fragment of the theme is heard again when Sam carries Frodo on Mount Doom. Here, the narrative significance of the leitmotif is more ambiguous: perhaps it is foreshadowing their eventual parting.

Unifying Music and Narrative

As theorized by Bribitzer-Stull (2015), the leitmotif blends two different “spaces” of analysis—the musical and the emotional—into a third, shared leitmotif space (10).

In terms of musical features, a leitmotif will be a recognizable theme or motive that we can define through tonal, formal, and textural contexts. The analyst can identify the development of its musical materials across its iterations.

In terms of emotional features, a leitmotif will have a blend of emotions comparable to the blend of emotions that exist within a single character at any given time, as shown through dramatic, textual, and visual (that is, non-musical) contexts. The emotions of the film will develop throughout the narrative.

When these two sets of features are blended together, it yields “musico-dramatic statements” and associations that “develop in tandem with musical and dramatic developments” (Bribitzer-Stull, 2015 12).

When defining the leitmotifs of a piece of media, it may be helpful to separate the musical and emotional features that are coming together to create the leitmotif by asking the following questions (Example 3):

| Musical features | Emotional features |

|---|---|

|

|

Development of Leitmotifs

Again, an important characteristic of leitmotifs is their musical development. Following is a list of developmental techniques common in film music leitmotifs (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 284-294), given in order from most to least common. Notice that many of the techniques have emotionally suggestive names—this is because leitmotivic development always signifies an emotional development in the narrative.

- Change of mode. A leitmotif that was initially introduced in major may be recast in minor, or vice-versa. This may accompany a development from a negative to a positive emotional state.

- Harmonic recontextualization. Leitmotifs are frequently reharmonized from their initial presentations. Certain recontextualizations are especially salient and emotionally charged:

- Harmonic corruption. A leitmotif that was harmonized with consonant harmonies (e.g., triads) may be “corrupted” through reharmonization with dissonant sonorities. Emotionally, this may indicate chaos, failure, corruption, betrayal, and so on.

- Harmonic redemption. A leitmotif that initially featured a prominent dissonance or chromaticism (for example, ♯4̂) is neutralized or resolved into consonance/diatonicism, signifying purification, peace, and so forth.

- Change of texture. A change in texture can accompany a similar change in the character; for example, a richly accompanied theme may be stripped down to a monophonic statement to show loneliness.

- Thematic truncation. Leitmotifs can be cut short dramatically, especially to signify death, fainting, or failure.

- Thematic fragmentation. A fragment of a leitmotif may sound to mark the introduction or departure of a significant dramatic element. In the former case, the fragmentation may foreshadow a later statement of the full leitmotif; in the latter, it recalls a full statement.

Other developments of leitmotifs are possible, but this list enumerates several possibilities to help start an analytical investigation. What’s always important is that the transformation has both musical and emotional components.

Bibliography

Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew. 2015. Understanding the Leitmotif: From Wagner to Hollywood Film Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316161678.