Intro to Film Music Analysis

Table of Contents

- Diegetic and non-diegetic music

- Pre-existing and newly composed music

- Functions of non-diegetic film music

- More examples for discussion

- Bibliography

Key Takeaways

This chapter will cover the following terms/concepts:

- Kinds of music within film:

- diegetic (happening in the film) vs. non-diegetic (only heard by the audience) music

- pre-existing vs. newly composed

- functions of non-diegetic music

Before we can analyze film music, you will need to be equipped with some specialized terminology for analyzing these media (film + music) together. Becoming familiar with this vocabulary will help you to better articulate your arguments about film music.

This chapter will make reference to a few different scenes as summarized below:

| Non-diegetic (heard only by audience) |

Diegetic (also heard by the characters in the film) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Newly-composed | • Jurassic Park theme • Parasite peach scene |

• Dreamgirls, “Love You I Do” |

| Pre-existing | • The Americans closing montage | • Guardians of the Galaxy Starlord dance |

Diegetic and non-diegetic music

Film music can be divided into two broad categories based on whether or not it exists within the film’s narrative. Most of the music we’ll focus on in our class will be non-diegetic music, and we’ll consider it together in context with the film itself, rather than as a standalone piece of music. But diegetic music is also important to understand.

Non-diegetic music

More colloquially, this might be referred to as the film’s soundtrack. A more specific definition is music whose source is not in the story (or diegesis) being conveyed by the film’s sequence of images (Levinson 2006, 143-144).

As an example, consider this scene from Jurassic Park (1993). The characters in this scene aren’t actually hearing this music; there is no orchestra on the island. This music is non-diegetic.

In the closing scene from the finale of the TV series The Americans (2013–2018), “With or Without You” by U2 plays as we see the characters for the final time. The song is heard by the audience, but no one within the TV show is playing the song on a record player or radio.

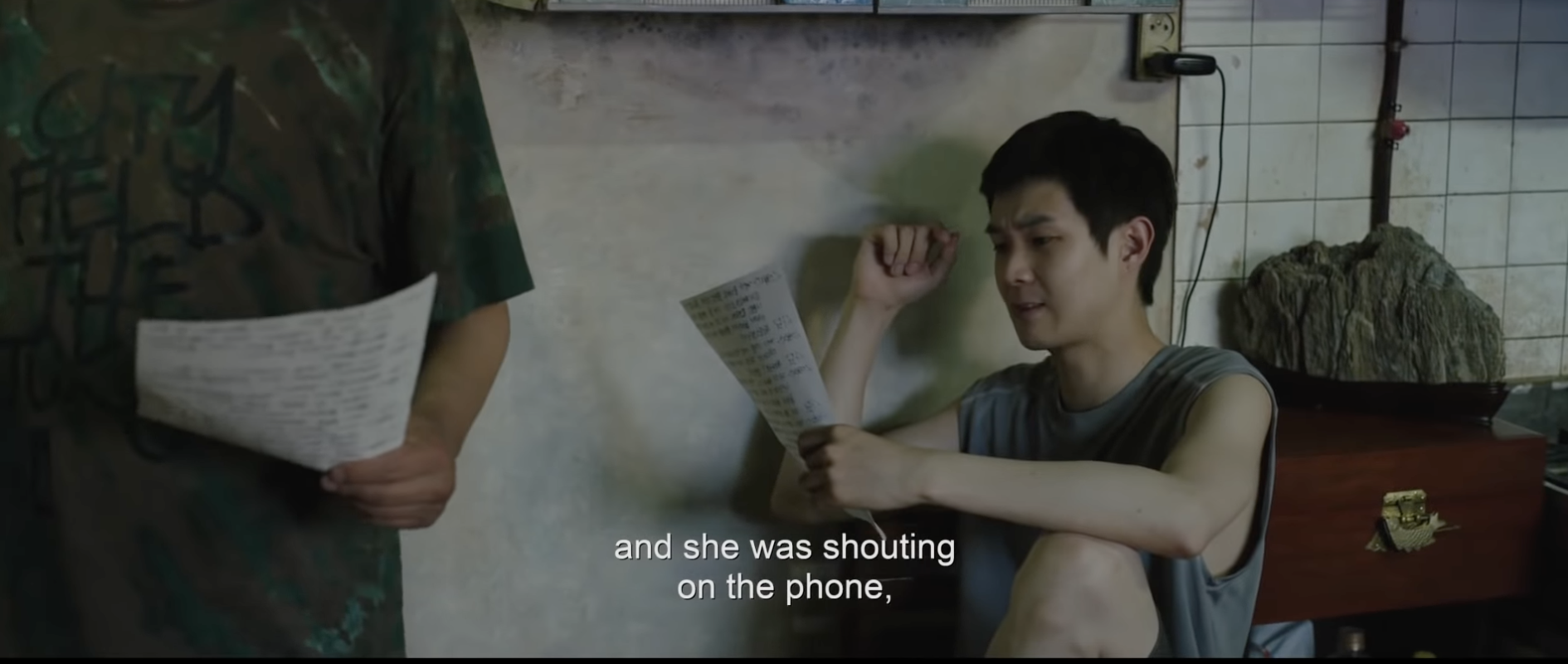

Non-diegetic music can be more subtle. Underscoring—”music at a low volume that serves as a sort of aural cushion for dialogue” (Levinson 2006, 145)—is another common manifestation of non-diegetic music, as in this Baroque-styled music composed for a scene in Parasite (2019). The focus here is on the dialogue, not the music underneath, and the music is not happening in the narrative.

Diegetic Music

Diegetic music is generated within the story and is hearable by the characters within the narrative of the film. The music may be played by a performing ensemble within the story or it may be a recording playing from a device.

Diegetic music is especially common in musicals as in the song “Love You I Do” from Dreamgirls (2006). The character is actually rehearsing this music within the narrative with musicians that we see performing alongside her.

The opening scene of Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) provides a good contrasting example where the music is not performed live, but heard on a recording. We see the main character put on headphones and press play on a Walkman to listen to “Come and Get Your Love” by Redbone (1974).

Some music may best be considered quasi-diegetic; for example, maybe the music transitions between categories, or maybe it is heard by the characters in the story but not in the same way that it’s being played in a story. For example, in a scene from Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005–2008), a character sings a song within the narrative, but we also hear backing strings and a pipa that do not seem to exist in the narrative world. This example blends diegetic and non-diegetic in a single instance.

Pre-existing and newly composed music

Much of what we consider to be film music is newly-composed. Of the examples in the discussion above, all the music is newly composed except the example from Guardians of the Galaxy. The music was written by the film’s composer(s), and generally speaking, the music was tailored to fit the scene in the movie, cut by cut.

Note that pre-existing and newly composed film music can both function either as diegetic or non-diegetic music, as shown above.

These different kinds of film scoring techniques lend themselves to different modes of analysis, which we will study in our course.

- For pre-existing music like the examples from The Americans or Guardians of the Galaxy, one should consider the intertextual associations that the audience may make between the music in its original context versus how it is deployed within the film, and what the filmmaker is communicating with that choice of music.

- For newly-composed music like the examples from Jurassic Park, Dreamgirls, and Parasite, we might consider a topical analysis or a leitmotivic analysis to specify what is being suggested about the narrative through the music.

Functions of non-diegetic film music

Music theorists are almost always concerned not just with labelling musical phenomena, but also describing how those phenomena function. In film music, we can think about what the score is achieving.

Following is an extensive list of possible functions of non-diegetic film music, adapted from Levinson (2006). It is possible you may be able to conceive of other functions, but this list should give you a solid basis for analysis. These functions are also not mutually exclusive—music may (and often does) exhibit more than one function at a time.

- Indicating a character’s psychological condition, emotional state, personality traits, or specific cognitions (e.g., the heroine is happy; the hero has realized who the murderer is)

- Modifying, qualifying, underlining, or corroborating a character’s psychological condition that is independently grounded by other elements of the film; in other words, the music emphasizes something that was already fully evident from other elements of the film (e.g., when the music tells you that a character’s grief over a loss is intense)

- Signifying of some fact in the film world other than the psychological condition of some character (e.g. a certain evil deed has occurred offscreen)

- Foreshadowing a dramatic development in a situation being depicted on screen

- Projecting a story-appropriate mood onto the scene as a whole

- Showing the viewer that events in the film are more important than those of ordinary life—the emotions magnified, the stakes higher, the significances deeper

- Suggesting how the viewer should feel about some aspect of the story (e.g., compassionately)

- Revealing how the presenter of the story or the filmmaker feels about some aspect of the story (e.g., sympathetically)

- Directly inducing emotions in the viewer (not merely suggesting them) such as tension, fear, wariness, relaxation, cheerfulness, sympathy, etc.

- Imparting certain formal properties to (parts of) the film, such as coherence, cogency, continuity, or closure.

- Distracting the viewer’s attention from the technical features of the film as a constructed artifact

- Embellishing or enriching the film as an object of appreciation

The following brief analyses of nondiegetic music show how these functions may be applied to the examples discussed earlier. Keep in mind that such analyses are highly subjective and rely on the interpretation of the analyst. Your own interpretation may differ!

Jurassic Park

This newly composed score performs several functions during the scene when the characters first encounter a dinosaur. It both underlines the characters’ feelings of awe and wonder (function #2), and suggests the viewer should feel the same way (function #7). Along these same lines, it projects a general mood of wonderment onto the scene (function #5).

The effect of wonderment is created through the use of a massive ensemble of orchestra and choir playing in a homophonic hymn-like texture (evoking worship/awe). The accompanying wide landscape shots and views of the dinosaur from a low angle similarly create a sense of expanse and grandeur that the music supports.

Parasite

The score in the peach-fuzz montage clearly evokes a Vivaldi-esque Baroque orchestral style (though it is actually newly composed specifically for this scene). Due to the rapid rhythms and polyphonic style, the music suggests that the composer put in difficult work to create an intricate piece of music with many moving parts working together to create a pleasing sound.

The music therefore signifies the same spirit in the film’s narrative (function #3), in which the members of the lower-class family are seen executing a carefully rehearsed plot to get the upper-class family’s housekeeper fired (with the eventual goal of hiring the mother in the lower-class family). The lower-class family painstakingly removes peach fuzz from peaches, rehearses and workshops scripted dialogue, and carefully times arrivals at certain locations at certain times to pull off their plot—these many parts of the plot work together carefully, like contrapuntal lines in a Baroque piece of music.

Another more practical function of the score is to bring unity to the montage (function #10), which, with its many cuts between different characters and settings, could otherwise struggle to hang together.

The Americans

In the finale of the final season of this TV show, the main characters, who are sleeper agents for the USSR, have run out their luck and need to evade arrest and flee to the USSR after living undercover in the US for decades. We see the family in disguises on a train to the airport, seated separately rather than as a family. They offer identification to police (the viewers, like the characters, are unsure whether the police are specifically looking for them). After the identification is accepted, the officers move on and the train begins moving again. The mother is idly looking out the window when she suddenly sees the daughter standing on the train platform, leaving her family to stay behind in the US by herself. The father sees her too, then promptly rises and quickly walks to sit next to the mother as a sense of shared grief overtakes the need to be discreet and avoid detection as a group.

The song “With or Without You” by U2 serves a few functions here. Most practical is that it helps supports the setting of the narrative (function #3): this song was a Billboard #1 song in May 1987, and the finale takes place in December 1987, at a time when the song would still have been on the radio and well-known by the public, so choosing this song helps establish a late-1987 setting.

The song also imparts a lot of emotional weight when the parents see their daughter on the platform (#2): at this moment, the lyrics in the song are replaced by vocalizations on “oh,” suggesting emotions that are too raw to be communicated verbally. When the lyrics do return, the meaning of the lyrics suggests several themes that can easily apply to the internal dialogue of the characters (#1): “you give yourself away”; “I can’t live with or without you” are sentiments that may be expressed either from the parents to the daughter or vice-versa.

More examples for discussion

Bibliography

Levinson, Jerrold. 2006. “Film Music and Narrative Agency.” In Contemplating Art, 143–83. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206179.001.0001.